7 Don’t Rush into Coding

7.1 Designing before coding

You have to believe that software design is a craft worth all the intelligence, creativity, and passion you can muster. Otherwise you will not look past the easy, stereotyped ways of approaching design and implementation; you will rush into coding when you should be thinking. You’ll carelessly complicate when you should be relentlessly simplifying—and you’ll wonder why your code bloats and debugging is so hard.

The Art of UNIX Programming (Raymond 2003) (Our bold.)

7.1.1 The urge to code

At the moment you receive the specifications for your app, it is tempting to rush into coding. And that is perfectly normal: we’re R developers because we love building software, so as soon as a problem emerges, our brain starts thinking about technical implementation, packages, pieces of code, and all these things that we love to do when we are building an application.

But rushing into coding from the very beginning is not the safest way to go. Focusing on technical details from the very beginning can make you miss the big picture, be it for the whole app if you are in charge of the project, or for the piece of the whole app that you have been assigned. Have you ever faced a situation in a coding project where you tell yourself “Oh, I wish I had realized this sooner, because now I need to refactor a lot of my code for this specific thing”? Yes, we all have been in this situation: realizing too late that the thing we have implemented does not work with another feature we discover along the road. And what about “Oh I wish I had realized sooner that this package existed before trying to implement my own functions to do that!”34 Same thing: we’re jumping straight into solving a programming problem when someone else has open-sourced a solution to this very same problem.

Of course, implementing your own solution might be a good thing in specific cases: avoiding heavy dependencies, incompatible licensing, the joy of the intellectual challenge, but when building production software, it is safer to go for an existing solution if there is one and it fits in the project: existing packages/software that are widely used by the community and by the industry benefit from wider testing, wider documentation, and a larger audience if you need to ask questions. And of course, it saves time, be it immediately or in the long run: re-using an existing solution allows you to save time re-implementing it, so you save time today, but it also prevents you from having to detect and correct bugs, saving you time tomorrow.35

Note also that assessing that a dependency/technology is a good choice for an application is not an easy task: there is a difference between thinking something will be the good choice and knowing that this choice is the correct one. Most of the time, when faced with a new technology, it makes sense to take some time to write a small prototype that tests the features we want to use. This process of prototyping small applications to test features is made easier notably by using the shinipsum package, which we will see in Chapter 9.

Before rushing into coding, take some time to conceptualize your application/modules on a piece of paper. That will help you get the big picture of the piece of code you will be writing: what are the inputs, what are the outputs, what packages/services can you use inside your application, how will it fit in the rest of the project, and so on and so forth.

7.1.2 Knowing where to search

Being a good developer is knowing where to search, and what to search for. Here is a non-exhaustive list of places you can look if you are stuck/looking for existing packages.

R and {shiny}

- CRAN Task View: Web Technologies and Services and CRAN Task View: Databases with R, which will be useful for interacting with web technologies and databases.

- The cloudyr project, which focuses on cloud services and R.

- METACRAN, which is a search engine for R packages.

-

GitHub search using

language:R: When doing a search on GitHub, do not forget to add the language-specific tag. - RStudio Community has a series of posts about shiny: questions, announcements, best practices, etc.

Web

- Mozilla developer center is one of the most comprehensive resource platforms when it comes to web technologies (HTML, CSS, and JavaScript)

- Google Developer Center also has a series of resources that can be helpful when it comes to web technologies.

- FreeCodeCamp contains more than 2000 hours of free courses about web technologies, plus a blog and forum.

7.1.3 About concept map

Using a concept map to think about your app can be a valuable method to help you grasp the big picture of your application.

Concept maps are a widely used tool, in the software engineering world and in many other fields. The idea with concept maps is to take a piece of paper (or a digital tool) and draw all the concepts that come to mind for a specific topic, and all the relationships that link these concepts together. Drawing a concept map is a way to organize the knowledge of a specific topic.

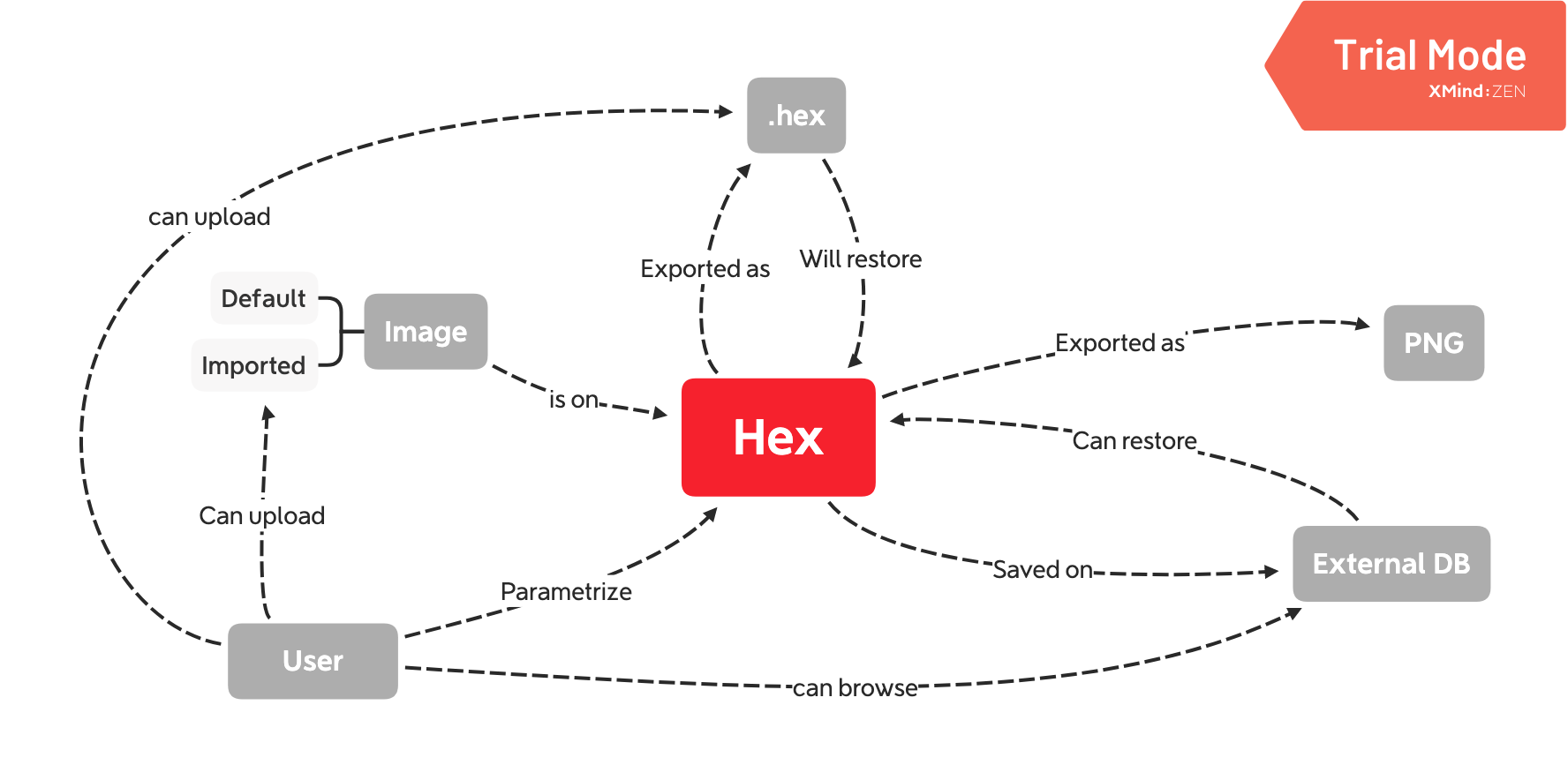

When doing this for a piece of software, we are not trying to add technical details about the way things are implemented: we are listing the various “actors” (the concepts) around our app, with the relationships they have. For example, Figure 7.1 is a very simple concept map of the hexmake (Fay 2023g) app.

FIGURE 7.1: hexmake concept map, built with XMind (https://www.xmind.net).

As you can see, we are not detailing the technical implementations: we are not writing the external database specification, the connection process, how the different modules interact with each other, etc.

The goal of a concept map is to think about the big picture, to see the “who and what” of the application.

Here, creating this concept map helps us list the flow of the app: there is a user that wants to configure a hex, built with a default image or with an uploaded one, and once this hex is finished, the user can either download it or register it in a database.

This database can be browsed and restore hex.

The user can also export a .hex file, that can restore an app configuration.

Once this general flow is written down, you can get back to it several times during the process of building the app, but it is also a perfect tool at the end to see if everything is in place: once the application is finished, we can question it:

- Can we point to any concept and confirm it’s there?

- Can we look at every relationship and see they all work as expected?

Deciding which level of detail you want to put in your concept map depends; “simple” applications probably do not need complex maps. And that also depends on how precise the specifications are, and how many people are working on the project: the concept map is a valuable tool when it comes to communication, as it allows people involved in the project to have visual clues of the conceptual architecture of the application.

But beware: very complex maps are also unreadable! In that case, it might make sense to divide into several concept maps: one with the “big picture”, and smaller ones that focus on specific components of your application.

7.2 Ask questions

Before starting to code, the safe call will be to ask your team/client (depending on the project) a series of questions just to get a good grasp of the whole project.

Here is a (non-exhaustive) list of information you might need along the way.

Side note: Of course, these questions do not cover the core features of the application. We’re pretty sure you have thought about covering this already. These are more contextual questions which are not directly linked to the application itself, yet that can be useful down the line.

7.2.1 About the end users

Some questions you might ask:

- Who are the end users of your app?

- Are they tech-literate?

- In which context will they be using your app?

- On what machines (computer, tablet, smartphone, or any other device)?

- Are there any restrictions when it comes to the browser they are using? (For example, are they still using an old version of Internet Explorer?)

- Will they be using the app in their office, on their phone while driving a tractor, in a plant, or while wearing a lab coat?

Those might seem like weird questions if you are just focusing on the very technical side of the app implementation, but think about where the app will be used: the application used while driving agricultural machines might need fewer interactive things, bigger fonts, simpler interface, fewer details, and more direct information. If you are building a shiny app for a team of sellers who are always on the road, chances are they will need an app that they can browse from their mobile. And developing for mobiles requires a different kind of mindset.36

Another good reason why talking to the users is an important step, is that most of the time, people writing specifications are not the end users and will either request too many features or not enough.

Do the users really need that many interactive plots?

Do they actually need that much granularity in the information?

Will they really see a datatable of 15k lines?

Do they really care about being able to zoom in the dygraph so that they can see the point at a minute scale?

To what extent does the app have to be fast?

Asking these questions is important, because building interactive widgets makes the app a little bit slower, and shoving in a series of unnecessary widgets will make the user experience worse, adding more cognitive load than necessary. The speed of execution of your app is also an important parameter for your application: getting a sense about the need for speed in your application will allow you to judge whether or not you will have to focus on optimizing code execution.

On top of that, remember all these things we saw in the last chapter about accessibility: some of your end users might have specific accessibility requirements.

7.2.2 Building personas

The persona is a concept borrowed from design and marketing that refers to fictional characters that will serve as a user type. In other words, a persona is a character that represents the “typical” behavior and traits for a group of users that will interact with your product.

A persona consists of a description of a fictional person who represents an important customer or user group for the product, and typically presents information about demographics, behavior, product usage, and product-related goals, tasks, attitudes, etc.

Quantitative Evaluation of Personas as Information (Chapman et al. 2008)

Using personas during the design process helps you center your focus on the end user, so that you know who you are creating the application for. Then, while building your application, you can think about how each persona will interact with a given feature: Will they use it? Will they understand it? Do we need to add extra information? Will they find this useful?

Asking these kinds of questions helps you take a step back from feature implementation and re-focus on what matters: we are building application for someone else, who will eventually use it.

The benefits of personas are that they enable designers to envision the end user’s needs and wants, remind designers that their own needs are not necessarily the end users’ needs, and provide an effective communication tool, which facilitates better design decisions.

Creating and Using Personas in Software Development: Experiences from Practice (Billestrup et al. 2014)

The building of these personas is made easier once you have interacted with the end users, as we suggested in the previous section. Given the answers to these questions, you will be able to draw some common characteristics about the future users of your application.

And don’t hesitate to detail these fictional characters as “[p]ersonas are considered to be most useful if they are developed as whole characters, described with enough detail for designers and developers to get a feeling of its personality”. (Billestrup et al. 2014)

7.2.3 Pre-existing code-base

From time to time, you are building a shiny app on top of an existing code-base: either scripts with business logic, a package if you are lucky, or a PoC for a shiny app.

These kinds of projects are often referred to as “brownfield projects”, in opposition to “greenfield projects”, borrowing the terminology from urban planning: a greenfield project being one where you are building on “evergreen” lands, while a brownfield project is building on lands that were, for example, industrial lands, and which will need to be sanitized, as they potentially contain waste or pollution, constructions need to be destroyed, roads needs to be deviated, and all these things that can make the urban planning process more complex. Then, you can extend this to software engineering, where a greenfield project is the one that you start from scratch, and a brownfield project is one where you need to build on top of an existing code-base, implying that you will need to do some extra work before actually working on the project.

When transforming brownfield projects, we may face significant impediments and problems, especially when no automated testing exists, or when there is a tightly-coupled architecture that prevents small teams from developing, testing, and deploying code independently.

The DevOps Handbook (Kim 2016)

Depending on how you chose to handle it, starting from a codebase that is already written can either be very much helping, or you can be shooting yourself in the foot.

Most of the time, shiny projects are not built as reproducible infrastructures: you will find a series of library() calls, no functions structure per se, no documentation, and no tests.

In that case, we would advise you to do it “the hard way”, or at least what seems to be the hard way: throw the app away and start from scratch.

Well, not really from scratch: extract the core business logic of the app and make it a package. Take some time with the developer(s) that built the current app, so that you can make them extract the core business logic, i.e. all the pieces of code that do not need a reactive context to run. Write documentation for this package, work on testing, and once you are done, call it a day: you now have solid ground for building the back-end, and it is built outside of any reactivity, is not linked to any application, and most of the time it can be used outside of the app. It might actually be more useful than you think: it can serve analysts and data scientists that will benefit from these functions outside of the application, as they can use the business logic functions that are now packaged, and so reusable.

Existing shiny projects, in most cases, have not been built by software engineers or web developers—they have been built by data analysts/scientists who wanted to create an interactive PoC for their work. The good news, then, is that you can expect the core algorithms to be pretty solid and innovative. But web development is not their strength: and that is perfectly normal, as it is not their core job. What that implies is that most shiny PoCs take shortcuts and rely on hacks, especially when it comes to managing reactivity, which is a beautiful concept for small projects but can be very complex to scale if you are not a software engineer by training; even more, given that R is by nature sequential.

That’s why it is better to split the business and app logic from the very beginning (as we have explained in chapter 3): it simplifies the process of refactoring a shiny PoC into a production-grade shiny application.

7.2.4 Deployment

There are so many considerations about deployment that it will be very hard to list them all, but keep in mind that if you do not ask questions about where your application will be deployed from the very beginning, sending it to production might become a painful experience. Of course, it is more or less solved if you are deploying with Docker: if it works in a container on your machine, it should work in production, but it is not as simple as that: for example, building a shiny application that will be used by 10 people is not the same as building an application that needs to scale to 50.000 users. Learning at the end of the project that “now we need to scale to a very large user base” might prevent the deployment from being successful, as this kind of scale implies specific consideration while building.

But that is just the tip of the iceberg of things that can happen. Let’s stop for a little story: once upon a time, a team of developers was missioned to build an app, and one feature of the app was to do some API requests. So far so good, nothing too complicated, until they discovered that the server where the app was going to be deployed does not have access to the internet, making it impossible to issue API requests from the server. Here, the containers worked on the dev machines, as they had access to the internet. Once deployed, the app stopped working, and the team lost a couple of days of exchanges with the client, trying to debug the API calls, until we realized that the issue was not with the app, but with the production server itself: and nobody in the team, not the developers or the client, thought about asking about internet access for the server.

It’s even more important to think about the IT side of your application, as the people writing specs and interacting with you might come from the Data Science team, and they might or might not have discussed with the IT team about deploying the app. There is a chance that they do not have in mind all of what is needed to deploy a shiny app on their company server.

For example, maybe your application has a database back-end. For that, you will need to have access to this database, the correct port should be set, and the permission given to the process that executes the shiny app to read, and maybe write, to the database. But, and for good reason, database managers do not issue read and write permissions to a database without having examined what the app wants to read, and how and where it will write. To sum up, if you do not want to have weeks of delay for your app deployment, start the discussion from the very beginning of the project. That way, even if the process of getting permission to write on the company database takes time, you might have it by the end of the coding marathon.